No matter if you greet the end of summer with jubilation or dread, this is typically the time when companies begin their strategic planning for the next year and beyond.

Despite the importance of having a strategic plan, many companies either struggle to achieve the goals, or worse, have no plan whatsoever.

‘Good’ companies have mastered both the planning and execution of strategic goals.

However, this doesn’t necessarily mean they are ‘great’ companies.

Understanding this distinction is the subject of a book I’ve been captivated by…entitled Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…and Others Don’t by Jim Collins.

There are hundreds if not thousands of good companies out there, but as the title infers rather directly, there are very few who are great. Collins and his team of researchers set out to understand the characteristics that separate the two.

It’s one of these characteristics or attributes that I want to really focus on today, specifically something called the Hedgehog Concept.

The name is derived from an essay by Isaiah Berlin entitled “The Hedgehog and the Fox” that itself is based on an ancient Greek parable. Essentially, the fox knows many things, and employs different strategies to capture the hedgehog.

Here’s where it gets interesting…

It’s easy to think since the fox has so many tricks up his sleeve, he’ll prevail by default. However, the hedgehog is really, really good at one thing, which is curling up in a ball where he becomes a bunch of sharp spikes that repels the fox in spite of his tricks.

Sounds almost like an episode of the Roadrunner and Wile E. Coyote, doesn’t it?

The parable is a reflection of two types of people or companies – one is scattered or diffused, never integrating their thinking into one unifying vision (i.e., the fox). On the other hand, the hedgehog simplifies a complex world into a single organizing idea or basic principal that unifies and guides everything.

Hedgehogs understand what is essential and ignore the rest, much to the dismay of the fox.

An example from the business world Collins cites in his book is the story of two drug stores: Eckerd (fox) vs. Walgreens (hedgehog).

Back in the 1970s and ‘80s, Eckerd executives were pursuing a strategy of growth and growth alone in which they would jump at any opportunity to acquire new stores, all with no rhyme or reason. They even purchased a home video company in 1981 with the belief that the emerging VHS market would propel them to new heights.

On the other hand, Walgreens had a very simple vision – have the most convenient drug stores with high profit per customer. The company took a systematic, consistent approach of only opening or relocating stores in specific, yet very convenient locations – corner lots with multiple ingress and egress options. In larger cities, they would cluster stores close together so no customer would have to walk more than a few blocks to reach one of their locations.

Can you see the difference?

Eckerd, which eventually ceased to be an independent company, would lurch after every opportunity to grow.

Walgreens would do something that seems counterintuitive on the surface – they would actually shutter stores that didn’t fit their model, even if doing so came at considerable short-term expense.

What Collins and his team eventually determined was that it wasn’t that specific strategy that made Walgreens great…

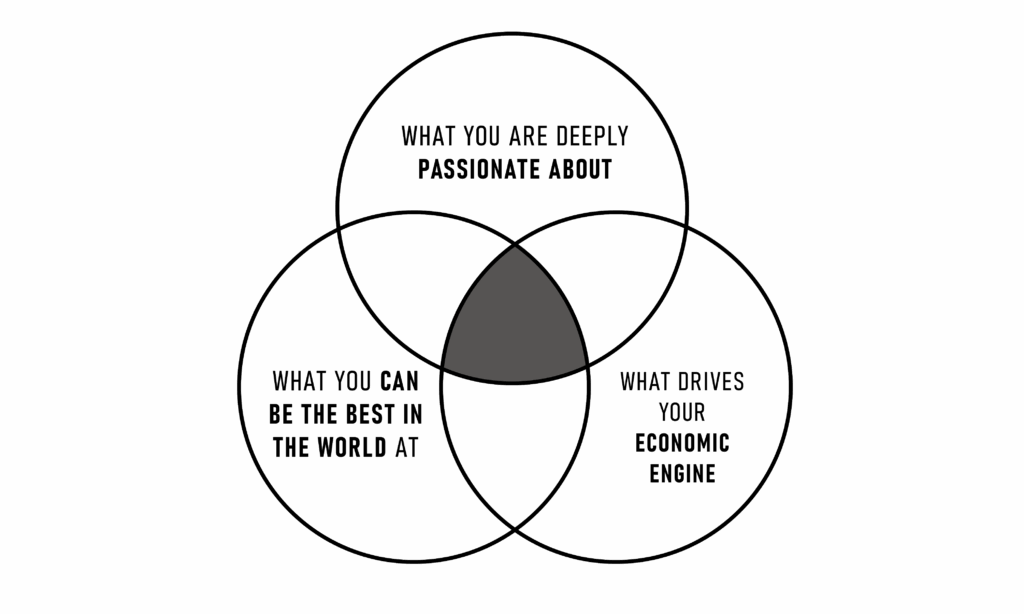

The company’s success was borne out of its mastery of what Collins and his team eventually dubbed the Hedgehog Concept, which they define as “…a simply, crystalline concept that flows from deep understanding about the intersection of the following three circles.”

- What can we be the best in the world at, and equally important, what can we NOT be the best in the world at?

This goes beyond having core competency, which you may be very good at, but not necessarily the best. Also, and this really caught my eye, it’s possible to be the best at something you’re not doing.

Known for his aversion to the banking industry, Warren Buffet wrote after his $290 million investment in Wells Fargo “They stick with what they understand and let their abilities, not their egos, determine what they attempt.”

- What drives our economic engine?

All great companies clearly understand how to generate sustained revenue and base profitability on a single denominator (i.e. profit per X).

For example, Walgreens flipped the conventional metric of profit per store to profit per customer visit, and in so doing, was able to increase both convenience and profitability at the same time. The company’s ‘convenience’ strategy would not have been possible with a profit per store model.

- What are we deeply passionate about?

Good-to-great companies only focus on activities they are passionate about. They don’t try to stimulate or manufacture passion, which is impossible, but rather discover what they are passionate about and pursue it vigorously.

Of all the companies Collins and his team evaluated, the key part of the Hedgehog Concept was passion. Instead of “let’s get passionate about what we do,” the great companies say “we should only do those things that we are passionate about.”

It’s the intersection of these three circles as shown in the graphic below that guided all of the great companies’ efforts.

The Hedgehog Concept is more fundamental or basic than ‘this is our goal(s) for the next 3 years.’

It’s even more fundamental or foundational than a mission or vision statement.

The Hedgehog Concept for a company is truly the litmus test to determine where you should be spending any time or money, much less assigning valuable people.

As the company’s leadership develops ideas for strategy, whether for a single year or multi-year, the Hedgehog concept will keep you within specific guardrails – should it be considered? Should it be discarded?

It’s not that great companies are inherently more disciplined or work harder, Collins explains. Both good and great companies had strategic plans, but the greats based their strategies and actions on a more disciplined understanding of their specific three circles.

Therefore, a company who strays outside that ideal intersection introduces risks – financial, reputational, operational – that can ultimately derail the long-term viability of the company.

ERM can play a valuable role in not only understanding their company’s three circles, but also identifying, assessing, and analyzing risks that inevitably lie between the current state and the desired future state of the company.

This proactive role is also another example how ERM differs from traditional risk management.

This is also perhaps the clearest example yet of why the risk management label may be obsolete for some.

The Good to Great… book was included on 2025’s list of top risk and strategy resources because it provides incredible insights into building great, resilient companies.

Coupling the Hedgehog Concept with ERM in a disciplined way can be a powerful tool for helping your company thrive in a VUCA world.

Is your company using the Hedgehog Concept or some other tool to set those guardrails on its strategy?

I’m interested in hearing your thoughts on the Hedgehog Concept or any other tools and tactics you use to zero in on the right strategic goals. Please feel free to join the conversation on LinkedIn.

Hedgehog Concept is just one of many different tools out there. If you’re struggling to find the best fit for your company’s needs, please reach out to discuss your current situation and potential options.

Featured image courtesy of Monicore via Pexels.com