In my years as both a risk practitioner and ERM consultant, there has and continues to be intense debate around methods for assessing risks. (If you are unfamiliar with the meaning of qualitative and quantitative, this article provides a quick overview.)

To illustrate this debate, take the following two comments from a previous article asking whether quantitative is the only future of risk management:

As you can see from just these two comments on a blog post, it’s interesting the different perspectives you will run into, and like so many issues in today’s world, some of comments I’ve come across can be a little on the mean side. (Why can’t people provide constructive criticism without being mean?)

Qualitative methods can be easier to implement and maintain, especially for companies without strong modeling and statistical analysis capabilities. As I’ve seen over and over, qualitative risk assessment is an option for many organizations starting out simply because they will be overwhelmed if they jump into a full quantitative approach.

This overwhelm can be a huge setback for any risk management initiative that can possibly take years to dig out from…

But as promoters of a quantitative approach contend, qualitative-based risk assessment can be fraught with biases and even be dangerous since you are relying on subjective impulses of the person(s) giving the score as opposed to objective numbers, or as psychologist and Nobel prize winner Daniel Kahneman explains:

Overconfident professionals sincerely believe they have expertise, act as experts and look like experts. You will have to struggle to remind yourself that they may be in the grip of an illusion.

Of course, I’m not going to argue too much about the shortcomings of qualitative assessments, especially when you throw heat maps and risk matrices into the mix, because it is true – there are certainly downsides to using the method, some of which I have personally experienced. Honestly, I haven’t attempted to use a heat map since the early days of my ERM career, because as Douglas Hubbard says in this presentation, tools like this provide no clear answer to the question “Should we spend $X to reduce risk Y or $A to reduce risk B?”

But when I speak with companies, it becomes clear how most of them simply aren’t equipped to take full advantage of quantitative risk assessment methods, modeling, and so on. Fortunately, I have found that…

There’s a middle way to obtain probability ranges without extensive statistics experience.

A strict qualitative assessment method that relies on a 1-5 or low-medium-high scale is certainly fraught with all kinds of pitfalls – I get it.

However, as I’ve explained in other posts, sometimes this is the best you’ll be able to do, especially in the beginning stages of any ERM initiatives. In this case, you do what you can, knowing and communicating that the method is not permanent. As the program matures and capabilities grow, you and executives will need to move into more sophisticated assessment methods.

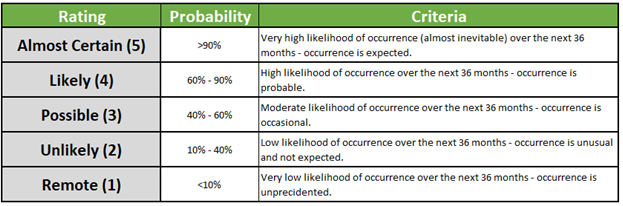

One approach that I use with some of my clients (…many of whom fall into this situation) is to assign specific criteria behind the scale/rating.

You see, one of the criticisms of qualitative (which I echo) is that the labels of “low”, “medium”, and “high” can mean different things to different people.

However, when you set probability ranges for each rating levels on the scale, or specific attributes behind what a level 3 impact means, you give the executive, manager, or information user a clear idea of what a specific ranking means in the context of a specific risk.

For example, when surveying the likelihood of risk(s) for a client, having probability ranges of <10%, 10-40%, 40-60%, 60-90%, and >90% can provide more clarity for decision-making. Again, simply saying the likelihood is a 3 or a 5 won’t help executives. It’s not perfect, but it is better than saying the risk has a “moderate” chance of occurring.

Pivoting to impact, let’s say you retain your 1-5 (insignificant-severe) scale but add different parameters on what a 3 means or a 2 means. For an example, your company relies heavily on computer systems to operate. A severe impact could consist of an “outage affecting > 25% of customers or unavailable for > 5 days” while an insignificant impact could be where an outage affects “…<1% of customers or Unavailable <4 hours.”

Of course, full quantitative methods where you have hard data to run models provides better insights on how a particular strategy, risk mitigation, or other idea could work out.

But according to Douglas Hubbard’s book Failure of Risk Management: Why It’s Broken and How to Fix It and the presentation mentioned earlier, there are several roadblocks to pursuing full quantitative assessment, with the most common being a lack of experience in statistics and modeling.

If that’s the situation you find your company in, a hybrid approach like the one described above can be a good first step for dipping your toe in the quantitative waters.

Regardless of where you’re starting out, it’s important that you’re always seeking to improve assessment processes since uncertainty will only continue to grow in the years ahead.

What have you tried doing to move your company from a qualitative to a more quantitative risk assessment approach?

I’m always interested in hearing more about what other risk practitioners are doing to help their organizations improve risk management processes. If you’re able to share your experience, do so by leaving a comment below or join the conversation on LinkedIn.

If your company is struggling to move beyond a basic qualitative approach or has found a strict quantitative approach too overwhelming, please schedule a call so SDS can help you move in the right direction.

Featured image courtesy of Airam Dato-On via Pexels.com