It’s fascinating to me how something as simple as words, especially ones used interchangeably, can create such confusion.

The English language is riddled with words that sound the same but have very different meanings, or what are known as homonyms. Examples include accept/except, bear/bare, or peak/peek/pique to name a few.

Perhaps as a native English speaker, I take some of this for granted. Putting myself in the shoes of someone learning English, it’s especially easy to see how this can breed confusion.

At times, even native English speakers can get confused at some of the words listed above!

Before diving into the serious part of today’s topic, I want to take a moment to share a humorous video connected to this idiosyncrasy of the English language.

While not homonyms in the technical sense, there are words in the ERM space that are used interchangeably, creating confusion.

One example we’ve discussed in the past is risk appetite and tolerance.

For the purposes of today’s article, we’re going to zero in on controls and mitigations. If you search these terms on Google, you may come away even more confused, especially since many non-ERM resources use these terms interchangeably. Although there is some overlap in their meaning and application, there does need to be some bifurcation or separation between the two.

Before getting into what these terms mean though, let’s establish when they come into the “risk management” equation.

At the conclusion of your risk analysis, you will need to determine the appropriate response to a risk.

However, it’s practically impossible to manage every risk, which is where ‘risk tolerance’ comes in. If a risk is at or below the company’s tolerance, then (additional) controls or mitigations are not needed beyond what is already in place. This situation, especially when the risk is below the company’s tolerance, represent the low-hanging fruit of opportunities.

Controls and mitigations are only relevant when the current state of a risk is above the company’s established tolerance or threshold.

I want to briefly highlight current state since many ERM resources promote the idea of inherent risk, which is a concept that is difficult and even impossible to understand.

Back to the topic at hand – the way I explain the difference between controls and mitigations to clients goes something like this:

Control – An activity with a specific design, is documented, and can be audited. As guidance from the Institute of Risk Management states, the intention of controls is to reduce the likelihood of a risk occurring. There’s also a set frequency to when they occur, and controls are more process-related.

Financial controls in connection with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act are one clear example of this, which has a strong connection with the COSO ERM Standard.

When I was working with a large U.S. company rolling out a new line of business, controls were developed around relevant laws, rules, and regulations. This was a particular risk category the company was extremely sensitive to managing.

One quick assumption about controls that should be made clear – there isn’t a 1-to-1 relationship between risks and controls. Many assume that there can only be one control for one risk, but the truth is that controls (…and mitigations, really) can be effective at reducing multiple risks, albeit at varying levels.

Mitigation – An activity that is more ad-hoc, not typically documented (or not as well-documented), and cannot really be audited.

While mitigations, like controls, can be executed before a risk event, they typically consist of things already in place to, as the IRM guidance says, reduce the impact of a risk.

Mitigations are typically focused in two areas: monitoring of the environment and activities that can be done in the future to limit the severity or damage a risk can inflict on the company should the risk event occur.

Mitigations are also more long-term in nature, in that benefits are not going to be immediate. To understand the effectiveness and how it accumulates, you’ll need to look over the long-term horizon.

Example Risk

Consider a company’s activities regarding a topic that is top of mind for many these days – cyberattacks. Some examples include:

- Firewalls, user access control, etc. – controls (these can be audited; pre-event)

- Monitoring activities in place – mitigations (harder to document that someone looked at a report; pre-event)

- Containment, disable remote access, etc. – mitigations (post-event; only able to execute after an event, no way of gauging effectiveness before an event)

When a breach does occur, these post-risk event mitigation steps will reduce the impact by locking down the network and isolating the potential data loss or damage to the company.

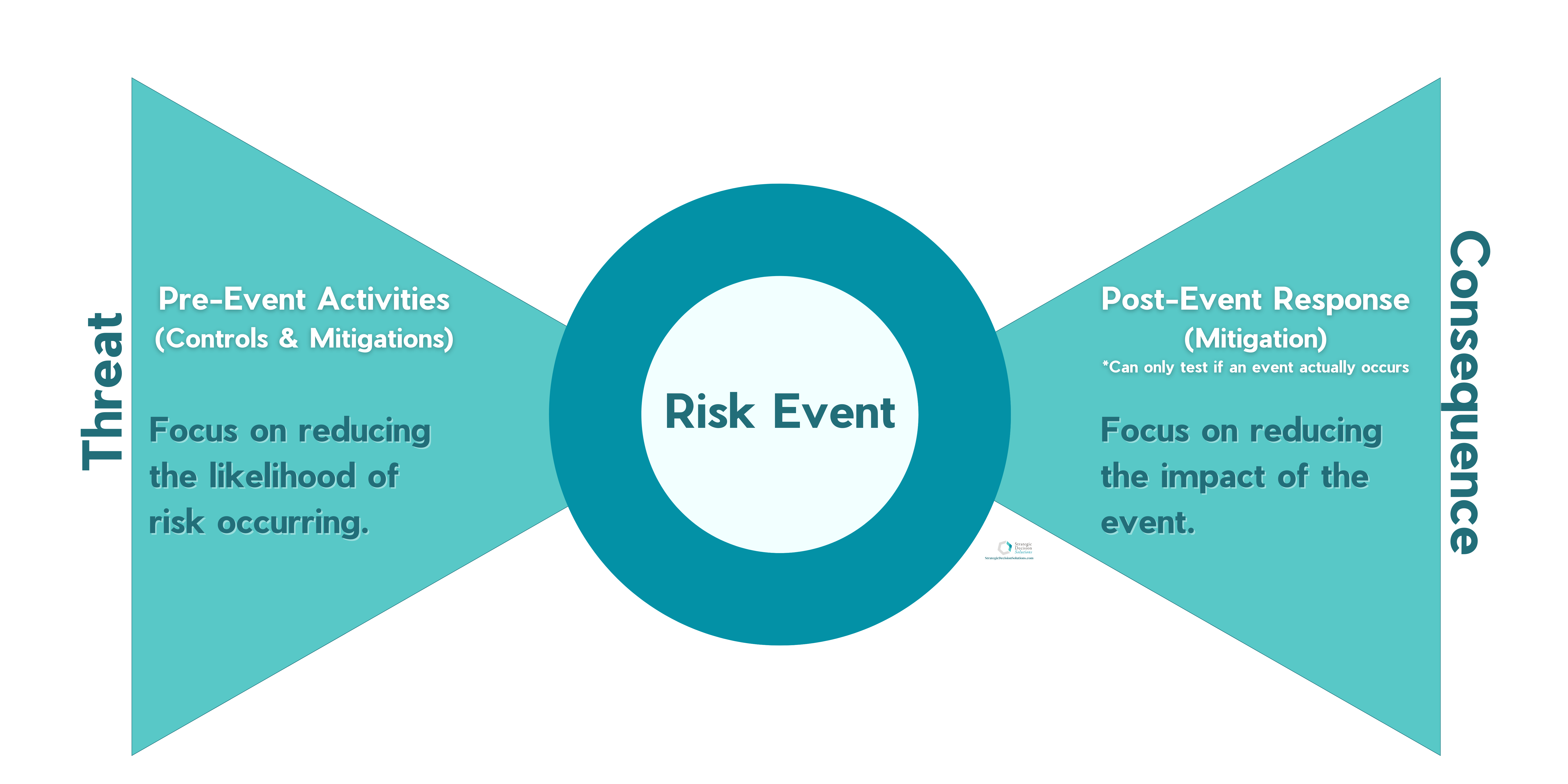

For all my visual learners out there, the following bow-tie graphic provides a great visual of where both controls and mitigations occur.

Notice that it is possible for mitigations to occur before a risk event. Unlike controls though, these ‘pre-risk event’ mitigations are things that are already in place that are serving another purpose but helping to defray the risk’s impact at the same time.

In this case, mitigations can consist of monitoring (i.e., KPIs, access reports, KRIs). If the business starts seeing trends, they can take steps immediately to nip the risk in the bud.

However, since this monitoring can’t be documented, and therefore verified by a third-party audit, it is considered a mitigation.

Understanding the effectiveness of controls

What often happens with risk controls is that once they’re in place, many consider that to be good enough.

However, a well-designed but poorly executed risk control, or vice versa, can be a tough thing to overcome.

Therefore, understanding the effectiveness of controls is an important part of a holistic risk assessment. Just because a business thinks their controls are effective doesn’t mean they really are.

An easy way for risk practitioners to do this on their own is to have a clear understanding of objectives and then monitor the risk each control is linked to.

This is why working with internal audit to understand the effectiveness of controls is so important.

As Norman Marks explains in his book World-Class Risk Management:

“[This partnership] does not remove the responsibility from management for ensuring internal controls are effective. Instead, internal audit provides a separate, objective assessment that should supplement management’s own monitoring of the effectiveness of internal controls (through supervision and other techniques).”

It should hopefully be clear the invaluable role that controls and mitigations play in handling risks that exceed the company’s tolerance.

Keeping these concepts separate, or otherwise refraining from using technical ERM lingo wherever possible, will help ensure these tools can be harnessed properly for maximum benefit to the organization.

What other risk management terms have caused confusion for you or your company?

Join the conversation on LinkedIn and share your experience on how seemingly interchangeable terms cause such confusion.

And if your company is struggling with enterprise risk management, reach out to me to schedule a call to discuss your company’s specific pain points and potential paths forward